“With comprehensive federal legislation […] state and local law enforcement investigating massage parlor trafficking networks will have the ability to more easily follow the money and build strong organized crime cases. And most importantly, traffickers will no longer have the strong incentive of a system that allows them to obscure their illicit activities.”

— Polaris [1]

Anonymous companies provide human traffickers the secrecy they crave. Opaque ownership structures make it difficult to track the individuals involved, while providing plausible deniability for those who profit from human trafficking operations. For example, the ownership of international shipping vessels is notoriously difficult to ascertain, making them the perfect vehicles for shipping human cargo with little chance of repercussion to the owner.[2] The criminals behind these enterprises can use the fact that their names are not connected to these companies to avoid punishment for their participation in these crimes.[3]

Numerous groups and individuals dedicated to ending human trafficking recognize the role anonymous companies play,[4] including Polaris, International Justice Mission, Shared Hope International, Street Grace, the Alliance to End Slavery and Trafficking (ATEST), and Humanity United Action.[5]

|

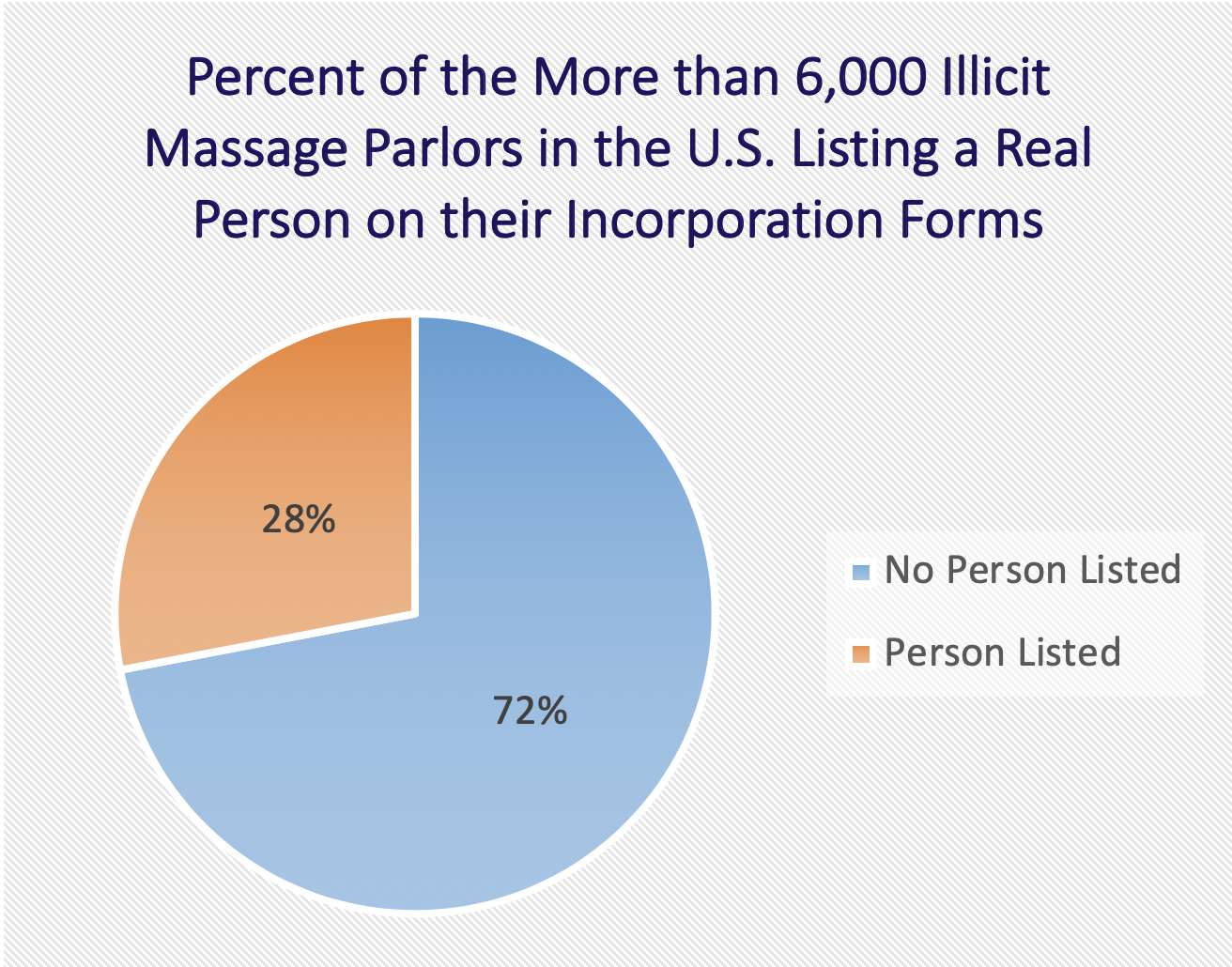

| Source: Polaris, 2018 [6] |

Anonymous Companies Mask the Ownership of Illicit Massage Parlors

A report by FACT Coalition member Polaris reviewed the ownership of more than 6,000 illicit massage businesses across the United States. Of those businesses, only 28 percent had a person listed on the business registration records.[7]

Anonymous Companies Perpetuate Modern Slavery

A Moldovan gang used anonymous companies in Kansas, Missouri, and Ohio in a scheme to lure foreign workers from Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and the Philippines into the U.S. with the promise of work at casinos and hotels. The gang then allowed the visas of the workers to expire and threatened to deport them if they objected to the substandard living arrangements; meanwhile, the gang withheld a large chunk of the workers’ earnings. [8]

Anonymous Companies Allow for Labor Exploitation

Owners of traveling sales companies use anonymous companies to hide the profits of their enterprise, simultaneously ripping off their employees by charging them for their lodging and food. Foreign employees are often threatened with deportation if they do not accede to demands or try to leave. Employees that do escape can find themselves miles from home with no money or resources. [9]

“Traffickers thrive in the shadows of our economy. They engage in this illicit activity because it is, sadly, profitable — a $290 million illegal industry in Georgia alone. Traffickers often hide behind the façade of legal businesses that, in fact, provide cover for the illegal activity. […] It is time to end the secrecy that allows traffickers to survive undetected and profit from their crimes.”

— Bob Rogers, CEO, Street Grace [10]

Anonymous Companies Help Human Traffickers Launder Money

Sex traffickers need a way to launder their profits. In one instance, launderers used two shell companies, Crown Venture Capital and Crown Venture Management. The laundered money involved proceeds from three Seattle-based illicit massage businesses: Aloha Tanning Resort, Malibu Tanning Spa, and Avalon Spa.[11]

Anonymous Companies Hide the Networks of Human Traffickers

Anonymous companies are deeply involved in labor and sex trafficking operations throughout Southeast Asia. Traffickers issue fake identity documents to foreign workers, threatening to expose their identities if they contact Indonesian authorities. Shell companies based in fishing ports in eastern Indonesia perpetuate these abuses by prohibiting fishermen from leaving their vessels or detaining them on land in makeshift prisons after the government’s 2014 moratorium on foreign fishing vessels. [12]

U.S. Is the Easiest Place to Establish an Anonymous Company

A 2014 academic study found that the U.S. is the easiest country in the world for terrorists and criminals to open anonymous shell companies to launder their money with impunity.[13] While Delaware has become infamous for its ability to recruit companies to register there, no state collects the names of the true (‘beneficial’) owners of companies. [14] Indeed, in every state, it requires less information to open a business than to get a library card.[15]

There Is a Bipartisan Solution

Two bipartisan measures — the Senate Anti-Money Laundering Act (S.Amdt.2198 to S.4049) and the House Corporate Transparency Act (H.R. 2513) — would require U.S. companies to disclose their beneficial owner(s) to the Treasury Department when they incorporate, and keep their ownership information up-to-date. Both bills have Administration support. A final version incorporating these provisions is under negotiation by the House and Senate and may be voted on as part of the “must-pass” FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

For more information, please contact Clark Gascoigne at cgascoigne@thefactcoalition.org.

Footnotes:

[1] Polaris, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” April 2018, http://bit.ly/2JEO4lB.

[2] Day, Michael, “Ghost ship with a human cargo,” The Independent, January 2, 2015, http://bit.ly/2LaZFuj.

[3] Polaris, “Hidden in Plain Sight”.

[4] See, e.g.: Letter from 15 Anti-Human Trafficking Organizations, December 12, 2019, http://bit.ly/2UkNkrv.

[5] For a full list of groups supportive of beneficial ownership transparency, please visit: http://bit.ly/2MKKedo.

[6] Polaris, “Hidden in Plain Sight”.

[7] Polaris, “Hidden in Plain Sight”.

[8] Global Witness, “The Great Rip-Off”, http://greatripoffmap.globalwitness.org/#!/case/57938.

[9] Polaris, “Knocking at Your Door,” July 2015, http://bit.ly/2km7phg.

[10] Letter from Street Grace, March 10, 2019, available at http://bit.ly/2WOoti6.

[11] Vanessa Bouche and Sean M Crotty, “Estimating demand for illicit massage businesses in Houston, Texas,” Journal of Human Trafficking, 2018, 4:4, 279-297, DOI: 10.1080/23322705.2017.1374080.

[12] U.S. Department of State, “2016 Trafficking in Persons Report – Indonesia”, June 30, 2016, http://bit.ly/2mfMzRi.

[13] Findley, Michael et al. “Global Shell Games.” Cambridge University Press (March 24, 2014), Page 74, http://bit.ly/2uTLptQ.

[14] Kelly Carr and Brian Grow, “A little house of secrets on the Great Plains,” Reuters, June 28, 2011, https://reut.rs/2PUcJUo.

[15] Global Financial Integrity, “The Library Card Project,” March 21, 2019, http://bit.ly/2VkOxvN.