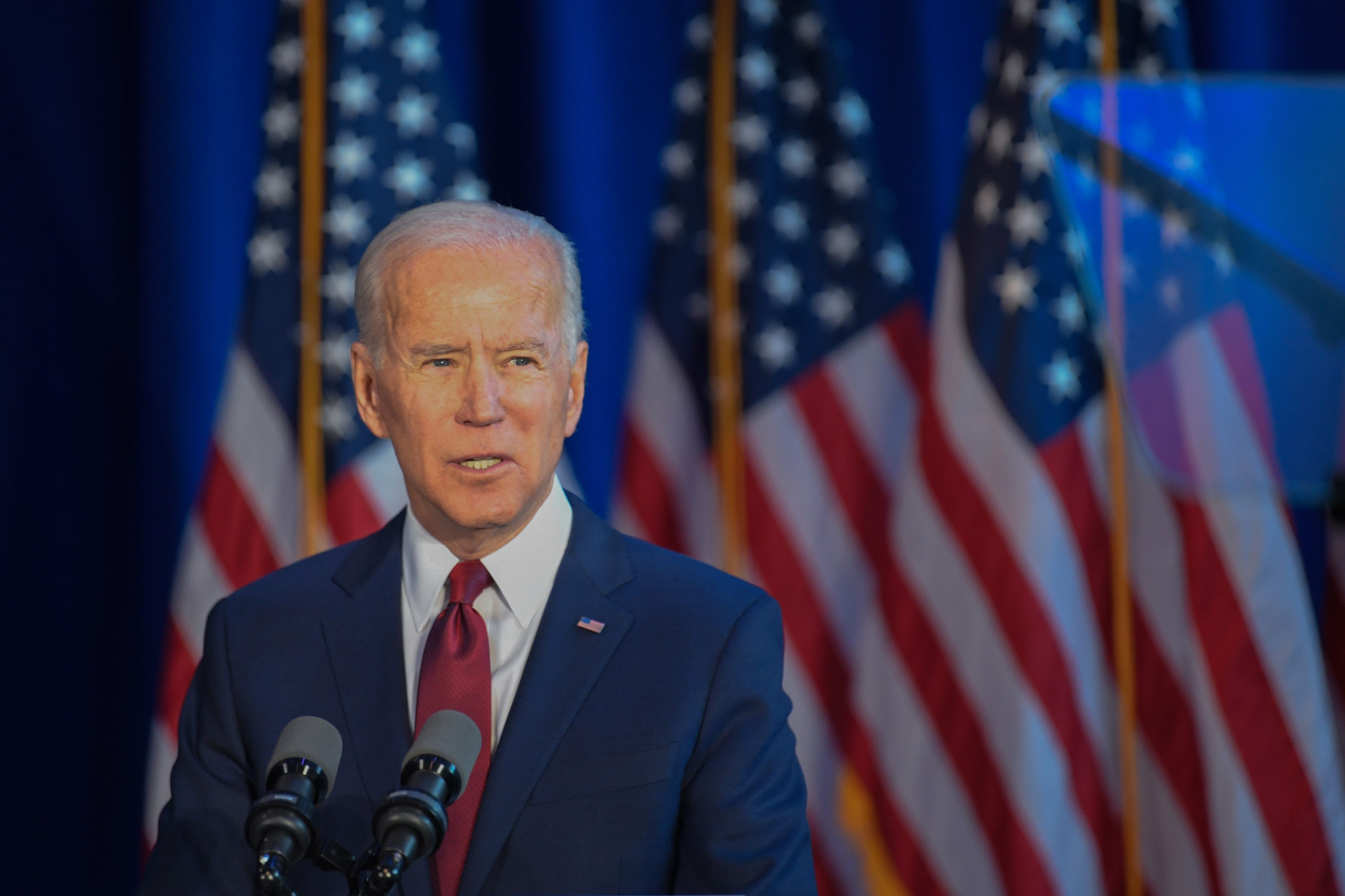

The United States has just delivered a clear message to the world’s kleptocratic elite: we’re back, and you’re on notice. The past few weeks have brought a whirlwind of developments toward the international anti-corruption agenda. President Biden has taken the first steps to fulfill his ambitious foreign policy agenda, enshrining commitments to strengthen global democracy and fight corruption in releasing a National Security Study Memorandum establishing anti-corruption as a “core national security interest” of the United States. The Administration likewise announced a $50 million emergency fund at USAID as a first step toward this commitment. The U.S. also made pledges at the G7 and UN General Assembly Special Session Against Corruption (UNGASS) likewise made pledges to counter corruption. Further, a new congressional caucus to fight foreign corruption and kleptocracy, launched amid this flurry of activity signals that Biden has bipartisan allies on Capitol Hill behind him. Yet, these commitments are only as strong as the U.S. government’s ability to deliver. The Biden Administration should work independently and with Congress to meet its grand foreign policy commitments to fight corruption abroad with anti-corruption reforms at home.

As the world’s largest economy and a prime destination of global investment, the United States has a unique role to play in the global fight against corruption. U.S. anonymous shell corporations have become a tool of choice for corrupt criminals and rogue states. Even without anonymous shell corporations, gaps in U.S. anti-corruption laws offer myriad other opportunities for foreign kleptocrats to funnel wealth through the United States. Lax real estate anti-money laundering duties have allowed the ultra-wealthy to buy up luxury condos as a store for ill-gotten gains. When measures like the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network’s geographic targeting orders (GTOs) shined a light on these behaviors in major cities, they simply took the practice to America’s heartlands. Our stock markets, too, have been marred by corrupt actors, as the FBI assessed with “high-confidence” in a leaked 2020 report. With so many places for illicit funds to hide, the U.S. “earned” the Tax Justice Network’s distinction as the second most financially secretive jurisdiction, right between the Cayman Islands and Switzerland.

Unlike these jurisdictions, however, the United States has huge potential not just to displace but disrupt corruption. The U.S. has unparalleled leverage against corrupt international actors who are “dependent on the global financial system centered on the American economy and its legal-regulatory apparatus,” including increasingly authoritarian states like China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Transnational criminals, meanwhile, tie the U.S. financial sector to illegal mining, terror financing, and human trafficking around the world, all of which create and thrive in corruption. Most encouraging, however, is that there’s strong reason to believe that the global community is ready to race forward again against corruption if the U.S. will let it. Just this month, the U.N. General Assembly met for a special session to signal its support for anti-corruption measures. And now, with the G7 meeting recently held in the U.K., the stage is set for the United States to pick up the transparency mandate some argue that Britain is abdicating.

It is time for the U.S. to initiate this positive, global chain reaction by accelerating its anti-corruption agenda, starting with policies already under consideration. The passage of beneficial ownership reform through the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) was a bold first step in uprooting foreign kleptocrats, underscored by the White House in its National Security Study Memorandum as well as in the UNGASS’ political declaration against corruption. Nevertheless, the Administration still has to finalize the rule before the January 2022 deadline legislated by Congress.

Strong implementation of the CTA still leaves other pathways for corruption, however. President Biden must also explore avenues to rout out ill-gotten wealth from U.S. real estate and private equity markets, the former of which Biden hinted at during the G7. Expanding the localized and temporary GTOs to be national and permanent would increase transparency in real estate transactions and remove the complexity of having different rules for different jurisdictions. Levying anti-money laundering obligations on registered investment advisors, meanwhile, would help scrub clean our $8 trillion private investment industry. Calling on existing legal authority, the Administration could move quickly on both of these additional measures without waiting for Congress.

This does not mean that Congress can rest easy, however; after all, the White House can only use the resources lawmakers have given it. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the case of FinCEN, the “tiny Treasury unit” with the monumental task of setting up a beneficial ownership registry. Congress must pass the additional FinCEN funding that Biden is asking for and several lawmakers are eager to give. Beyond funding, Congress should also use new platforms such as the Caucus against Foreign Corruption and Kleptocracy to supply the Administration with new tools and hold it to account when it fails to use them. These are all simple measures that will have an immediate effect on schemes of global kleptocrats, bringing relief to the entire nations that they pillage. Quashing avenues for corruption through U.S. financial markets would in turn allow U.S. foreign aid dollars to go further, as currently up to 30 percent falls into corrupt hands. Good governance abroad would also have a knock-on effect of improving transnational security, making the U.S. more secure. For too long, Washington has left these advantages on the table by enabling global kleptocracy. But now, there is a rare opportunity to clean up corrupt flows if lawmakers and the Administration can come together to back up their words with meaningful policy.