A new report shows the boom is not doing enough to address Boston’s acute affordable housing crisis and will accelerate economic inequality in the city.

An earlier version of this article was posted by the Institute for Policy Studies.

Boston is being transformed by a luxury housing boom. A decade from now, the city’s skyline and population demographics will be fundamentally altered by decisions being made today.

This boom has clear benefits, providing jobs in the building trades and increasing property tax revenue for the city. And the city has negotiated for affordable housing set-aside or linkage funds from some projects. But the boom is not doing enough to address Boston’s acute affordable housing crisis and will accelerate economic inequality in the city.

Suffolk County is the most unequal county in Massachusetts, which is the nation’s sixth most unequal state in terms of the gap between the wealthiest 1 percent and everyone else. And Boston’s racial wealth divide will only worsen if current trends continue. One marker of those trends: In 2015, not one single home mortgage loan was issued for African-American and Latino families in the Seaport District and the Fenway, two Boston neighborhoods with thousands of new luxury housing units.

City officials celebrate the construction of luxury properties such as the 61-story One Dalton Place. But there are reasons to be alarmed. These towers play an accessory role in a global wealth system that’s hiding wealth and masking ownership.

With European countries now insisting on greater levels of corporate transparency, illicit cash is now cascading into the United States. Many analysts believe the U.S. is the now world’s second-biggest tax haven and secrecy jurisdiction after Switzerland.

In response to this tends, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has increased scrutiny over real estate markets in Miami, New York, and parts of California, Texas, and Hawaii. But Boston doesn’t appear on the FinCEN network watchdog list, a status that may make Boston more attractive for secret cash.

Luxury condominiums in Boston are a form of “wealth storage.” In a new study that I co-authored, we examine twelve luxury condo towers in Boston, with 1,805 units at an average price of over $3 million. Over 35 percent of these units are owned by limited liability companies (LLCs) or trusts that mask the real owners and beneficiaries. Almost 40 percent of the LLCs owning Boston luxury properties have organized themselves in the state of Delaware, the premiere secrecy jurisdiction in the United States.

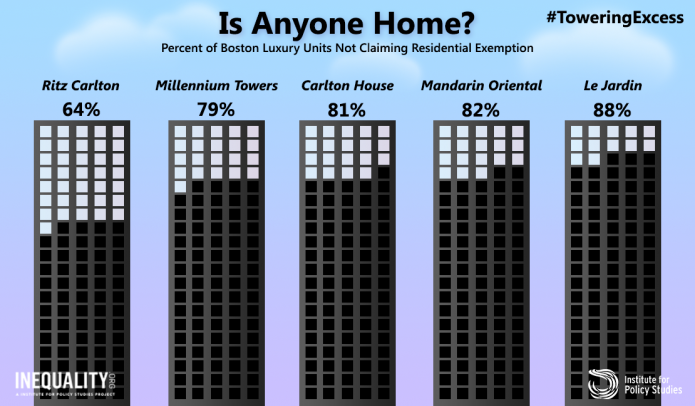

Of these 1,805 luxury units, 64 percent do not claim a residential exemption, a clear indication that the condo owners are not using their units as their primary residence.

Some luxury buildings stand out as textbook “wealth storage” properties. The 51 condominium units above the Mandarin Oriental Hotel at the Prudential Center, for instance, sold for an average of $6.5 million. Over 56 percent of these units are owned by trusts, LLCs, or shell corporations, and fewer than 18 percent claim a residential exemption. The Millennium Tower has 443 units averaging $2.4 million in assessed value. Over 35 percent are owned by shell corporations and trusts, and almost 80 percent of the units do not claim the residential exemption. Half of the LLCs that own units at Millennium Towers are organized in Delaware.

Boston’s previous and current city administrations have encouraged these thousands of new luxury units now in the pipeline without properly exploring the perils these units pose. Luxury construction drives up the cost of land in central neighborhoods, with a ripple impact on the cost of housing throughout the city. Affluent, but not superrich, households in Boston find themselves pushed to outer neighborhoods, increasing competition for scarce affordable and moderately priced housing.

Bringing more millionaires and billionaires to Boston will exacerbate an already grotesque inequality of income, wealth, and opportunity. New residents of these buildings will likely be wealthy white U.S. nationals and international buyers from European and Asian countries in the global 1 percent, compounding the extreme racial wealth divide that already exists in Boston.

Luxury projects such as One Dalton Place press for the construction of a new fossil fuel energy infrastructure at a time when Boston should be moving aggressively to transition toward 100 percent renewable energy in order to meet our clean energy commitments. The city should require all future luxury properties should be state of the art “net zero carbon emissions” green construction, not requiring any additional fossil fuel inputs.

There are other things Boston should to do protect its non-wealthy residents and capture some of this global wealth to fund city services and affordable housing. In exchange for providing a safe haven to global capital, Boston should tax real estate transactions on properties selling for over $2.5 million and dedicate revenue from that taxing to the city’s affordable housing linkage fund.

Boston could discourage high-end vacant properties by taxing buildings that sit empty for more than six months a year. We can learn from other jurisdictions such as Vancouver and Washington, DC, that have created incentives for building owners to house people, not wealth.

Boston should require property owners, as part of recording deeds, to disclose the actual human being who owns the property. Boston real estate should pass the “library card test.” Getting a Boston Public Library card — a task that requires full disclosure of identity and a real address — should not be harder than creating a shell company and using illicit funds to purchase a luxury condo in Boston.

Now is the moment for a rigorous debate about whether the luxury building boom helps or harms Bostonians. We should question the assumption that the benefits of these luxury towers will trickle down to reduce inequality and expand affordable housing. The burden of proof falls on the city and policymakers to show there is no harm.